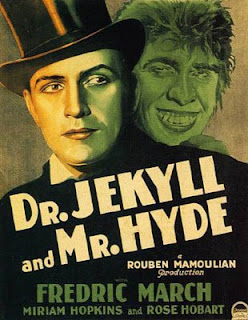

Since its first publication in 1886, "Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" has never been out of print. Stage adaptations began the next year, 1887, and the first film version was released in 1910. By one count, there have been 123 film versions in all. In both stage and film versions, the same actor is traditionally cast in both roles, and the high point of the drama is the "transformation scene" in which Jekyll becomes Hyde. Happily, many of these are now available on YouTube; you can see the earliest surviving film version from 1912, along with the performances of Frederic March, John Barrymore, Spencer Tracy, Boris Karloff, and even Bugs Bunny.

Since its first publication in 1886, "Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" has never been out of print. Stage adaptations began the next year, 1887, and the first film version was released in 1910. By one count, there have been 123 film versions in all. In both stage and film versions, the same actor is traditionally cast in both roles, and the high point of the drama is the "transformation scene" in which Jekyll becomes Hyde. Happily, many of these are now available on YouTube; you can see the earliest surviving film version from 1912, along with the performances of Frederic March, John Barrymore, Spencer Tracy, Boris Karloff, and even Bugs Bunny.

It's too bad, though, that nearly every version of this story has Mr. Hyde physically looking monstrous. The stage transformations, of course, relied more on the actors' ability to manipulate their expression, stance, and movements, but nearly every film gives Hyde fangs, hair, and a hunchback. This misses the whole point of Stevenson's story, which is that Hyde's "deformity" was inward; no one who saw him could quite put their finger on why his appearance made them suddenly want to kill him. Simply put: Mr. Hyde walks among us, or perhaps within us, and there is no sure way of detecting the transformation from the respectable to the detestable.

Perhaps we all have "secret selves." After all, we're social creatures, and there's no reason we should act or feel the same when we are in different company, or by ourselves. But the million small acts of repression required to shape our social identities can't help but have some effect on our psyche. These repressed thoughts may surface briefly in dreams or nightmares, may spur the creativity of artists. Indeed, some performers, such as Marilyn Manson, Screaming Jay Hawkins, Ghoulardi, or the Gravediggaz, have made careers out of wearing their horror on their sleeve. We can then be reassured when we see that, off stageand out of makeup, these performers are "nice" people -- but what of the reverse? What of those who, though outwardly nice, respectable citizens, are leading double lives, in one of which they are cheating on their partners, betting on dogfights, frequenting prostitutes, or gambling away their life savings?

So perhaps Jekyll and Hyde are, more or less, symptoms of civilization, a double metaphor for what we must all do to survive in a world of pressures and performances. The common view is that the Victorian society of Stevenson's day was far more restricted and repressed than ours; no wonder such men created monsters! Or are we just as repressed, perhaps even more so?

Is Jekyll and Hyde a story for its time, or for all time? What parallels do you see between the psychological world it presents and the world of today? How far from us, in 2014, is that decrepit old house with its mouldering green door? And who of us has the key?